See no evil, hear no evil: Accessibility shortfallings during lockdown

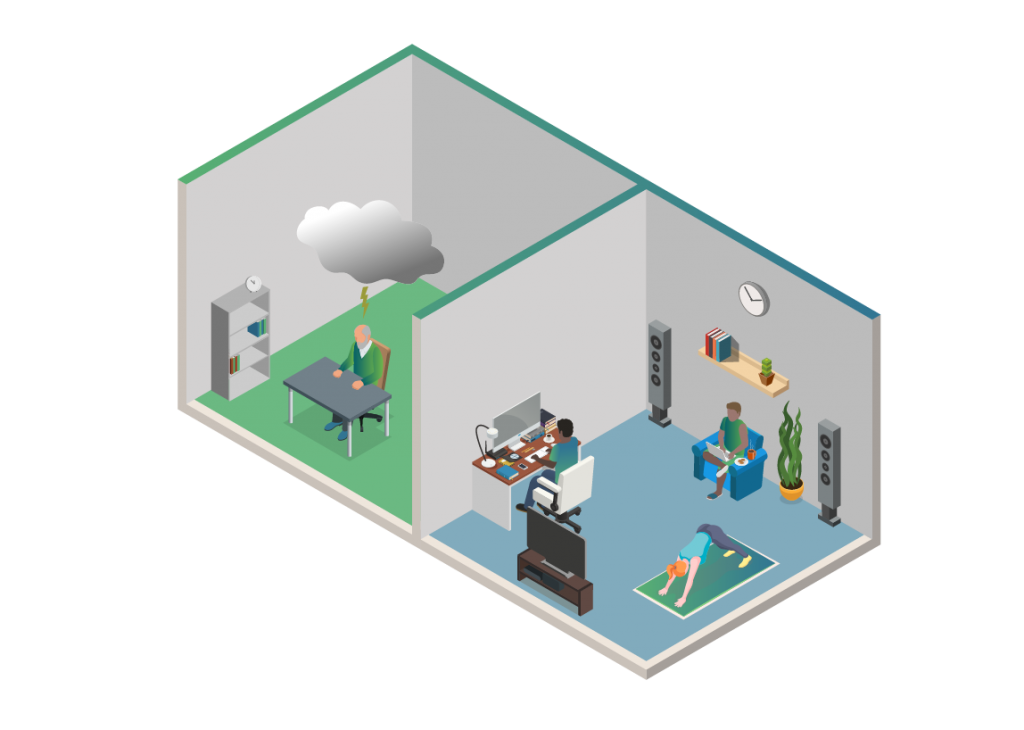

Lockdown has been a huge change for us all. But while many of us switched relatively smoothly to home working, online socialising, and socially distanced shopping, for others it’s been a different story.

For many people with disabilities, lockdown has meant increased isolation. Poor software accessibility features and the reconfiguration of public spaces have compounded the usual issues that disabled people face in everyday life.

So what are the barriers, and how can they be overcome?

Online accessibility

Take technology. We’ve all been forced to rely on it more during lockdown – but is it really accessible to everyone?

Researcher Tim Hart explored the various options on video conferencing packages for hearing-impaired and deaf people. He found that voice recognition features on most platforms are inadequate.

Another option is to use a separate voice recognition app – but these often don’t link effectively with the video conferencing software. Captioning or subtitling are alternatives, but may be available only at an extra premium, or might even require a hearing person to type up the conversation in real-time.

Paradoxically, some disabled people say the move to virtual communication has opened up their worlds by levelling the playing field. They can now participate in virtual museum tours, gigs, social events, university classes and religious services from their own homes.

Physical accessibility

In fact, there are several ways in which lockdown ought to benefit those with visual or mobility impairments.

Social distancing is one: it should mean more space for everyone. However, as visually impaired activist Amy Kavanagh explains, the reality is often quite different.

She writes of the difficulties in maintaining a two-metre distance when sighted people won’t give her space. Her experiences are backed up by a survey from charity Scope, which found that a quarter of disabled supermarket shoppers had experienced negative attitudes from other shoppers during lockdown.

Other barriers include one-way signs in supermarkets that are impossible for those with sight loss to follow; changed layouts in public buildings, bewildering those visually impaired people who rely on familiarity to get themselves around; and fears that train staff will be reluctant to physically guide passengers in need of assistance.

According to Dr Kavanagh, the assumption seems to be that “disabled people just stay at home anyway”.

She writes: “The most frustrating thing is that unlike Covid-19, many of these access barriers have solutions. Putting tactile bumps in the floor markers in supermarket queues would help me find them, if staff are given PPE, they can support me on public transport.

“The government needs to remind everyone that disabled people have an equal right to participate in society and it just takes a few small adjustments to make it safer for us all.”

Adapting to the unfamiliar

Even those who are able-bodied may struggle with lockdown and our new socially distanced environment.

People with autism, learning disabilities, dementia and other conditions can find it hard to adapt to a rapidly changing world.

That leads many to stay home in isolation, particularly as social care services such as day centres have been cut during lockdown.

Decision-making

Of course, lockdown was implemented as an emergency. But the lack of provision for disabled people demonstrates an age-old truth: they’re left out of decision-making.

As Dr Kavanagh writes: “My biggest worry is that this new much-used label of ‘vulnerable’ is obscuring the real societal barriers that will make exiting lockdown impossible for disabled people. Yes, the virus is a risk, but so often inaccessible infrastructure and negative public attitudes create the real challenges to disabled people being able to participate in society.”

As we exit lockdown, we have the chance to do better. We can introduce software that empowers rather than excludes. We can redesign our streets and buildings to take into account everyone’s needs.

Above all, we can try to overcome prejudice and involve disabled people in the conversation about how society should be rebuilt for everyone’s benefit.